A regrettably late quarterly report...

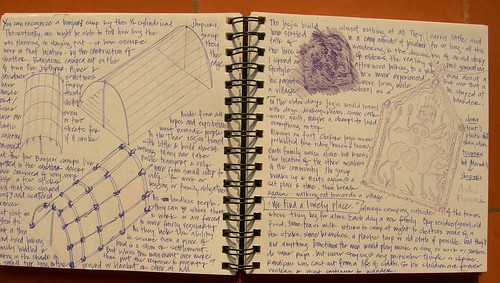

I am trying to not think about my time in Africa as a complete failure. It wasn’t a waste of time but things certainly did not really go as planned. I can honestly say that I don’t think I learned much at all about Toureg tents, about their ideas of space, family, land and community.

Of course, I can now speak at great length about economic challenges to herders and Saharan nomads, about wells and water politics, about camels and the salt trade, about the flooding of the Niger River, about political turmoil and Komeni and the Toureg rebellion and an ongoing demand to keep slaves, about food aid and poverty and tourism.

The material that I gathered and the project that emerged, despite my attempts to make things “work” and stay on track, was not so much based on clear data or even clear stories and lives of people, as it was a discovery of emotions and relationships, of things that cannot be measured accurately or explained fully. I will never be sure how much I glimpsed of Malian or Toureg culture and how much I projected on the people I encountered. I left with several charged experiences that I have no way of explaining.

The four countries that I visited in Africa left such completely different impressions that I have a hard time grouping them together into any sort of coherent “African experience”. I still laugh at the irony that the location where my project seemed the most set, where I had by far the best contacts and logistical planning, where my expectations were the highest was the greatest disaster. You can’t plan everything. And no one can make the rains come or make the heat break before it is ready.

I realize that I had been traveling, physically moving to a new location, a new community (or lack thereof), a new bed, on thirty three of my first sixty days in Africa. And this included a fourteen day stint in Essaouira and nearly two weeks in Bamako. This cannot be healthy.

There must be an optimal pace for movement according to the land and social specificity. But this is not it. Nomads move slowly, gently. They tend to move together - in families, in clans. Or if traveling solo - a man or a boy leaving with herds and then returning periodically like a ship gone out to sea and coming back to port. It is important to return, to rejoin.

I never intended to run like that, but it was some fever that took hold of me and kept me moving, that wouldn’t let me settle. My restlessness climaxed and was only exacerbated by a series of difficulties which made each resting place seem particularly undesirable. Things will be better once I leave Bamako. Things will be better once I get out of Mopti. Things will be better once I am in a village and out of Timbuctou. In retrospect, the situation was even more telling because it was unintentional.

A bit of ongoing illness mixed with a smattering of personal violence, a heavy heap of abuses and intimidations, a few bruises, and some witnessed ugliness did little to make me want to stay in with my reluctant hosts. I wanted to make things work, but after washing blood off of my hands and wiping the spit from my face, I realized it was time to leave. There are just too many places in the world far more beautiful and welcoming for me than Mali in the hot season. So, I ran off to Amsterdam and luckily I arrived at the Academic Medical Center Polikliniek Tropische geneeskunde just before my dysentery fully jumped to my liver.

Now I find myself in Ireland flying through the last phase of my project. Things feel remarkably easy. I am in a country where everyone speaks English, the land is fertile and beautiful, where it cools down in the evening and where a long bus ride is only 4 hours. Some of my best “interviews” have taken place over a few pints in the local pub while a band plays at a nearby table. There are local Traveller groups all over the country and wonderful people who have been very patient and open to talking with me about their lives.

The settlement of Travellers, conditions of halting sites, and general accommodation issues are something that everyone in Ireland seems to have an opinion about. Not only does this make my job easier, but it shows that the situation means something to people, people care about the answers to questions I am asking, they want me to understand their side of the story and how the issue is present in their lives. Opinions are strong and filled with personal stories.

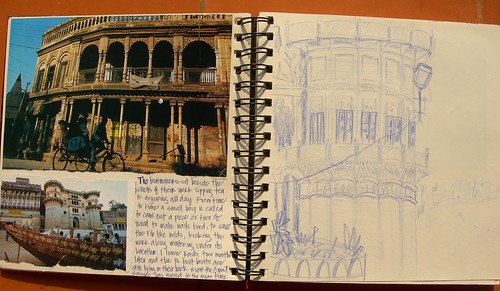

This week, I have been meeting with several women over at Traveller Visibility Group in Cork City. Over many hours worth of tea and scones we traded stories of living on the road. The conversation bounced back and forth between Cork, Galway, Mongolia, and Rajasthan with the women asking many questions about the other nomadic groups I have been living with and pouring over some of my photographs that I brought along.

I leave Cork this afternoon to cycle out around Kerry for the next week, visiting halting sites and eventually ending up at the Carimee Horse Fair in Buttivant, a major meeting for Travellers from all over Ireland.

My health has been steadily improving, and I am taking lots of time to write, process, and enjoy Ireland and my remaining time with this project before I return to the states. I am trying to slow my pace a little, but time continues to move quickly.